…and beyond! The Crime Bus now sails under the Esotouric flag, offering bus adventures into the secret heart of Los Angeles. Kindly visit our new site for the scoop on exciting new tours like James Ellroy Digs LA, Raymond Chandler’s Los Angeles, John Fante’s Dreams of Bunker Hill, Reyner Banham Loves Los Angeles, Hotel Horrors and Main Street Vice.

Raymond Chandler in the 1940 census

There’s something perverse and delicious when mundane formality captures genius in its net. The census is one of the best tools for illuminating these queer intersections.

The recently published 1940 US census finds the serial renters Raymond and Pearl (Cissy) Chandler living at 1155 Arcadia Avenue in what was then Monrovia Township. Their monthly rent is $50. (Regrettably, for those who like to visit the residences of great writers, the house has not survived; much of the block was replaced by condominiums in 1979.)

Mrs. Chandler, who answered census taker Cornelius F. Hax’ questions, gives her age as 63 (she was actually 69) and Chandler’s as 51. She states that during the week of March 24-30, 1940, Chandler spent 36 hours engaged in his profession, Free Lance Writer. Yet when asked about employment during the calendar year 1939, she states that Chandler did not work at all.

This report of an idle 1939, like her age, is a lie. Chandler worked fiendishly that year. His first novel, The Big Sleep, was published in February. He began, then set aside The Lady in the Lake and dug into Farewell My Lovely.

By the time the census taker knocked on their door on April 8, the revisions for Farewell were nearly complete; it would be published in October. Perhaps Chandler was in his study working while Cissy spoke with Mr. Hax in the front of the house. Maybe, ever conscious of their privacy, she pulled the door shut behind her and answered his questions on the porch. As is nearly always the case with these dry census records, one is left longing for more. A few facts, most of them wrong, jotted down, and then Mr. Hax was off to knock on another door.

In walking his route that spring day, Mr. Hax recorded a cross-section of the suburban west. The Chandlers’ neighbors came from California, Italy, New York, Nebraska, Wyoming, Ohio, Maine, Pennsylvania, Canada, England, Texas, Missouri, Illinois, Massachusetts, Arkansas, Iowa, Minnesota and Montana. There was a painter and a telegraph operator, a chicken rancher and a bookkeeper in a meat packing plant (Chandler, when new to California, had done similar work in a dairy), an automotive mechanic and a U.S. Postmaster, a wholesale shoe salesman, an architect, a department store saleslady, a machinist, a comptometer operator, a stenographer, a teacher, an attorney and a man who kept an aviary.

As he began what would be the most distinguished and lasting literary career of any writer working in the debased genre of detective fiction, Chandler chose to live modestly among strangers, far from L.A.’s literary or intellectual hum. Hollywood wouldn’t call for a few years yet.

The Chandlers kept to themselves. He wrote. She looked after him. He was still sober. They had fourteen more years together. And the purple San Gabriels loomed above.

A moment in time: Beth Short in the 1940 census

On April 10, 1940–seventy-two years ago today–a man named Edmund M. Hart walked the streets of Medford, Massachusetts in the county of Middlesex, knocking on doors and making inquiries about the people who lived behind them. He was the designated U.S. Census enumerator, and the personal information he gathered has just this month been placed online.

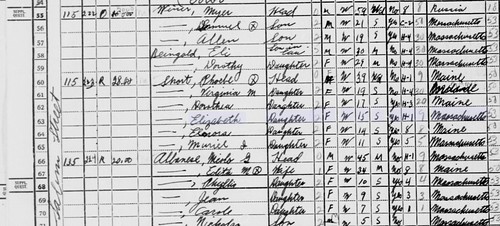

On Salem Street, at number 115, Hart recorded the particulars of three separate households.

The owner of the property (valued at $5000) was Myer Winer, aged 59. A widower, he lived with his sons Samuel (21) and Allen (19), his daughter Dorothy (29) and her husband Eli Reingold (30). The young people were all born in Massachusetts, Myer Winer in Russia. He was a tailor in a retail clothing store, earning $700 for the previous year (for only 18 weeks work). Son-in-law Eli Reingold was employed as a clerk in a wholesale tea company, earning $1200 for the previous year (52 weeks). His wife, a stenographer for the Commonwealth of Massachusetts, earned the same wage for her 52 weeks of work. Although the census did not ask, we know from other sources that theirs was a Jewish family.

Paying $35 in monthly rent was Edwin F. Jones, 58, and his wife Minnie, 56. He was from Maine, she from Massachusetts, and both had been living in the same house for at least five years. Jones was a newspaper printer, with wages of $2350 for the previous year (47 weeks work).

It is the third and final family which draws our attention, for reasons having nothing to do with their quiet life in Medford, Mass. The head of the household is Phoebe Short, 39, native of Maine. She tells Mr. Hart that her family of six has been living in this place for at least five years, and pays $28 rent–$7 less than Mr. and Mrs. Jones, perhaps a reflection of Myer Winer’s charity. Although unemployed, she has an unspecified income of more than $50, not from wages. This is, we assume, money provided to her by her estranged husband Cleo.

Living with Phoebe are five unmarried daughters. Virginia M. (19), is the only one seeking work outside the home, claiming 34 weeks unemployment through the end of March 1940. Her occupation is given as New Worker, meaning she had left school but had not yet secured any position. The other Short sisters are all in school: Dorothea (17), Elizabeth (15), Elenora (14) and Muriel J. (11).

Although history records that Phoebe Short’s husband Cleo was still living, she identifies herself to the census as a widow. Maybe at this time, Phoebe really thought her husband was dead. Maybe she claimed to be a widow instead of admitting to a stranger that she had been abandoned. We do not know if the story she told Edmund Hart was the same one that she told her landlord and her daughters. The bare facts of the census record cannot reveal the nuances of any family’s tragedy.

Phoebe’s pretty daughter Elizabeth (15) is frozen in time by the census keeper’s ink. She is still safe with the women who know and love her, still free to walk out the front door on a balmy day and turn west on the Salem Road, which is will not for some years be bisected by I-93, a highway which seems to have obliterated 115 Salem Street. Half a mile from her home, past the movie theater and the city hall, is the old Salem Street Burying Ground, a neglected cemetery dating to the late 17th century. Maybe she wandered there, among the winged skull markers and crumbling walls, and thought about her own mortality and imagined the joys her life would contain before the grave.

She’s still a couple of years away from her ill-considered escape from the limited opportunities available to a poor, fatherless girl in the Boston suburbs. When she runs, she will go to California, to be reunited with Cleo Short. Their relationship will quickly fracture, and she will become a vagabond, moving often and forming short-lived, intimate relationships with strangers. She will travel from California to Florida, to Chicago, then west again. She will lie to her mother, and she will not look for work. She will sink into depressive obsession over a promising relationship cut off when the man dies in a plane crash. She’ll make some foolish choices, and some stupid ones.

And at 22, they will find her body cut into two pieces, naked and brutalized, in a vacant lot in Los Angeles. She will find posthumous fame as the beautiful victim of one of the most heinous unsolved crimes in American history. They will call her The Black Dahlia, leer over the terrible photographs, and they’ll never stop talking about her.

But for this moment, she is still frozen in time. The census taker knocks on the door, and wants to know: who is the head of this household? What are the names of the children, and their ages?

Elizabeth Short is 15 years old, and it is springtime. The possibilities are limitless. And we are far away, and remembering a girl we never knew.

Thank you, Joe Cianciarulo, for the detective work.

The Garden of Allah in the 1940 census

Hollywood in its Golden Age was filled with beautiful, glamorous apartments, residence hotels and bungalow courts, quite a few of which have survived the harsh winds of time, neglect, temblors and the questionable taste of subsequent owners.

But the site of that most storied of all the Hollywood residences, the legendary Garden of Allah (8152 Sunset Boulevard), is today a bland mini-mall anchored by a McDonald’s restaurant in the post-modern style. Popular myth has it that it was demolition of the Garden of Allah and its beautiful pool and fountains, mature gardens, handsome villas and culture of creativity that inspired Joni Mitchell to write “Big Yellow Taxi” — “they paved paradise, put up a parking lot.” If that isn’t true, it ought to be.

Photo: Los Angeles Public Library

The Garden of Allah fell to the wrecker in summer 1959. But on April 9, 1940, when the census enumerator dropped by to take the hotel’s temperature, it was at its height as an urbane social center, the only place suitable for a certain class of extraordinary person to make their Hollywood home.

The census record is illuminating and more than a little heartbreaking as a suggestive portrait of a vanished time. The first resident recorded is practically a novel in a single line:

Lerner, Herbert A. White, single, Louisiana-born, 29. His residence on April 1, 1935? ” At sea. Near Florida” Occupation? “First mate, private yacht.” Annual wages $1200.

This is the type of fascinating stranger one might make a friend of at the famous bar at the Garden of Allah. No wonder writers loved the place.

And yes, there are famous writers living at the Garden of Allah in the spring of 1940, and we’ll get to them, but just look at the variety of elevated humanity that was drawn to this seductive corner of the world.

A stock broker. A public utilities executive. A couple guys in advertising. Varied and sundry magazine hacks. A night club publicity manager. An actors’ agent. Alonzo F. Farrow and wife Edna, who run the joint ($3600/year for him). British film producer John Stafford. The beautiful Greta Nissen, a silent star that fell from favor, though not entirely, due to her strong Norwegian accent. Populist historian and pulp writer Harold Lamb, who must have been a hoot over a cup of grog. Irish novelist Liam O’Flaherty, slumming with film work. Edwin Justus Mayer, who wrote To Be or Not To Be.

And mostly clustered together near the bottom of the page, those grand Algonquin wits. George S. Kaufman, theatrical writer, 50, who declined to state his income. Robert C. Benchley, motion picture writer, $5000+ per annum. Alan Campbell and wife Dorothy P., for Parker, both movie writers, both earning what friend Benchley brings home. This was where the hard work got done, and steam was let off, before the cycle began again. What nights they must have had, and what days, beneath the ridiculous California sun, surrounded by geniuses and nincompoops, the lovely and the lost.

Once upon a time in Hollywood, this place was real, not imagined. Now it’s just real estate, a ring of shaggy palm trees around an asphalt lot. Pull in some time, park in the center, close your eyes and just breathe the air that once fed paradise. That grand moment has passed, and this moment can be rude and trying. But a more beautiful world is coming. It was ever thus.

Photo: Los Angeles Public Library

Downtown Los Angeles, 1946: Beth Short’s last walk

Here’s another amazing discovery from the good folks at the Internet Archive. This May 1946 night time process shot through Downtown Los Angeles was filmed by Columbia for the Rita Hayworth vehicle Down to Earth. In the picture, the actress portrays the ancient Greek Muse Terpsichore, who visits 20th century America to torment the Broadway producer who dares put on a show portraying the muses as man-crazy sluts, and Terpsichore herself as “just an ordinary dame.” Sacrilege!

It’s a fitting theme for us here at 1947project. For while perturbed Terpsichore was no human female, we think she’d sympathize with the posthumous plight of Beth Short, Black Dahlia murder victim, brutalized before death by unknown assailants, and ever after subject to vile, false rumors. (No, she wasn’t a prostitute. Our offshoot Esotouric offers a bus tour explaining who she really was.)

Now thanks to Down to Earth, we have this gorgeous footage of the heart of Beth Short’s post-war city, a bright, populated and thriving Downtown that is as lost to us as the cultures of the Inca or the Toltec. Click “play” and enter a place that positively thrums with energy. Marvel at the neon lights, the late-night coffee houses, the fur shops, the airline offices, the swimsuit-clad manikins, the drug stores, the theaters of Broadway (some open all night), the street life. Gasp at Clifton’s Pacific Seas (demolished 1960, now a parking lot) and Clifton’s Brookdale (still with us, but indefinitely closed for renovations), boggle at Alexander & Oviatt’s bright-lit windows packed with the hautest of gentleman’s couture, and laugh when you spy unmistakeable evidence of just how huge a star Miss Rita Hayworth was in the spring of 1946.

Beth Short spent the last half of 1946 living in Los Angeles, bouncing from cheap hotel to friends’ couch and back again. Her social life centered on the nightspots of Hollywood and Downtown. This process footage contains a near-exact recreation of her final steps on the night she vanished: south along Olive Street away from the Biltmore Hotel, then left on Eighth Street, where we are rewarded with two astonishingly rare views of the Crown Grill, the last place she was seen alive.

Knowing what we do, the stylized crown above the bar’s entrance looks an awful lot like a death’s head, doesn’t it?

As a time travel portal, this clip rates among the finest. Blow it up big on your screen, sit back with a cup of something soothing, and be transported.

1947project’s L.A. history presentation at Occidental College

On March 6, 2012, social historians, bloggers and tour guides Nathan Marsak and Richard Schave spoke to students in Dr. J.B.C. Axelrod’s History 395 course “Reading and Writing L.A.” at Occidental College about their work on the 1947project time travel blogs, including On Bunker Hill, and the many ways of telling the many stories of Los Angeles.

The Black Dahlia and the News of the World

After 168 years of publication, today”™s edition of the News of the World is that scandal-plagued English tabloid”™s last.

The collapse of a major newspaper is fascinating to watch unfold, but any suggestion that this is an unprecedented media scandal the likes of which has never before been seen is, simply, balderdash. Take away the trapping of modern media tools, and the situation in the News of the World newsroom is revealed to have been nearly identical to what was happening in 1947 Los Angeles, during the investigation of the murder of Elizabeth Short, AKA The Black Dahlia.

The News of the World folded, not because it lacked readers, but in a desperate effort by Rupert Murdoch”™s News Corporation to deflect political fallout from an escalating newsroom phone hacking scandal that included interfering in the investigation of the murders of children and spying on the families of dead soldiers and victims of terrorism.

Top British politicians appear to have had knowledge of these crimes and to have been intimately involved with some perpetrators. Further, editors have confessed to paying large sums to the Metropolitan Police for scoops on celebrities and crime victims. The scandal is an evolving thing, with fresh revelations coming by the hour.

Popular opinion holds that the entire working staff of the paper has been sacrificed to save the skin of former editor, current News Corporation chief executive, Rebekah Wade, an intimate of Murdoch and of Prime Minister David Cameron. Meanwhile, the entire affair is subject to passionate commentary by rival journalists, stalked celebrities and the scandalized public via Twitter and other social media.

But how does this relate to the Black Dahlia and 1940s yellow journalism?

For Rupert Murdoch, powerful and much-despised king of the yellow media, read William Randolph Hearst, whose Examiner was the best capitalized paper in post-war Los Angeles, and whose reporters did much more to further the Black Dahlia murder investigation than anyone else, including the detectives of the LAPD. For ruthless Murdoch editors Andy Coulson and Rebekah Wade, read Hearst”™s top execs James Richardson and Aggie Underwood.

For the Metropolitan Police, implicated in the current privileged-information-for-cash scandal, read the Los Angeles Police Department, who were so deep in Hearst”™s pocket that they didn”™t balk when Examiner city editor James Richardson invited detectives to join reporters in the newsroom for the opening of murder victim Elizabeth Short”™s missing luggage, which a reporter had located at the downtown Greyhound station and illegally purchased from the bag check desk. The evidence inside was promptly photographed for publication in the paper, and only then was handed off to detectives.

For Milly Dowler”™s long-suffering parents, newly victimized by the news that their kidnapped daughter was not alive and deleting her own mobile phone messages in 2002, but rather her phone was being checked by News of the World hacks, read Phoebe Short, Elizabeth”™s mother, tricked into telling a telephoning reporter all about her 22-year-old daughter with the ruse that Elizabeth had won a beauty contest. Only when she had nothing left to say did the reporter confess that in truth her daughter had been found naked and hacked in two in a vacant lot.

In both instances, 1947 Los Angeles and 2011 London, the motivation was the same: to sell newspapers, and advertising, by appealing to the most base instincts of the general public. Then as now, people are fascinated by stories of sex and violence, and willing to pay for the publication that gives them seemingly factual information they can”™t get elsewhere. Reporters have always been able to justify their intrusions by laying their work on the altar of Truth. And unscrupulous publishers have always been willing to pay whatever it takes to hack into private lives of public people, to feed the information hunger.

As the dust settles in England over this latest manifestation of a very old story, the real question is why gossip is so powerful a thing, alluring enough to make fortunes and bring down empires. Why are we so interested in other peoples”™ private lives?

A LAVA Sunday Salon extra: Nathan Marsak on L.A. Noire

Interesting/Painful

The Great Day is upon us.

Few weeks back I penned a review of LA Noire which has since had a few thousand page reads. Our piece generated interest only because I’d played the game so early. Still, must confess to being enamored of the reaction it received.

It can be interesting/painful to read was the standout: in that my historical interpretation was interesting, as such must infer painful did not connote my words were mere product of yr average monograph-producing dullard whose role as an academic historian serves no-one but his colleague. Don’t get me wrong””most of my work is performed for a small circle in allied studies””but the social function of critiquing LA Noire I take as a solemn task. In any event, I’m going to consider painful as synonymous with challenging. (“Blogging” Noire makes the process all the more important and aggravating…that I subconsciously include but consciously reject Sherman Kent’s Writing History; never thought I’d have to grapple with that.)

My critique of Noire resulted in a little behind-the-scenes action, as you might imagine. Actually, I don’t know what you might imagine. Probably some dime-novel enantiodromia: “Rockstar worked so hard on recreating the world of 1947 Los Angeles, they may’ve well given us a game about dragging an oxcart through the Duchy of Lotharingia.” Nope, never implied that, nor did R* have to send their dime-novel goons after me either. Rather, now that the reviews are coming in fast and furious, it looks like they have their issues. And I have mine. Overall, me and the conventional reviewer are both quite positive. I, however, represent that previously unthought-of, unrecognized, and underutilized market: the first-time gamer. Who knew?

Anyway…as I aimlessly occupy myself like everyone else for said game to be released in a coupla hours, we’ll amuse ourselves by playing “Critique the Critiques!” (Which I must admit is rather pointless as everyone who might read this once it’s posted will be glued to their consoles, chasing bad guys up Main St.)

It’s a really interesting article; it’s quite critical of the game in terms of minute geographic accuracy, but the nature of the criticisms he makes seem so picky that it’s clear that in the broad sense, at least, the city is very accurately recreated. If his complaints are mainly that signs exist that didn’t exist until the early 50’s, or that there were stairs rather than a road at a certain intersection, I feel pretty confident that they got the big stuff right.

Which is a fascinating statement. Naturally, I would counter with the dusty old Miesian idiom “God is in the details.” I mean, Rockstar’s consumed with the Gesamkunstwerk here, and you’re going to let the details slide? Hey, I warned y’all. I self-confessed to nitpickery in my own text. To continue:

GotDAMN, I think they’re almost expecting too much out of the game with some of those nitpicks, and also don’t seem to have a firm grasp on the concept that videogames are still very much limited by the hardware. I will commend him on the amount of information in that article, but it’s a little overboard IMO. And with no mention of the face capturing tech + hiring all these actors to actually play their parts, someone should tell him that the huge budget he mentioned couldn’t all go towards recreating a perfect 1947 LA brick by brick.

I got that he still enjoyed it, but I feel like maybe if he stated some of his complaints in front of the Rockstar reps, they could’ve or should’ve explained how they couldn’t afford to focus on recreating a 100% perfect city because they’re building a GAME, and not a 1947 LA simulator. While he does point out that he pushed the “game aspects” to the background for that article since that’s not where his areas of expertise lie, I think doing that does a disservice to just how much work the team has to do when making all this stuff.

I’d like to hear his opinion of the game after he puts 20 hours into it, and whether or not he’s still looking at what’s NOT there instead of the whole picture.

I see where you’re coming from, but he explicitly noted he had no idea about video games or the industry, and was really only brought in to sample the world, not the game.

I think he was credited as a consultant too, so he probably invested considerable emotion regarding the ultimate recreation of LA.

I agree with everything said above: quite sure I’m expecting too much, nor do I have a firm grasp on anything, plus LA can’t be recreated brick by brick, and no, it’s not a simulator, etc. On the other hand, in case it didn’t come through, I want it known that I laud Team Responsible to no end. Could I have constructed such a world? Hella course not. Let it be known I am eternally grateful and thankful to those who did. Now, will I be a “whole picture” guy after twenty hours of gameplay, as to which commenter above alluded? We’ll see.

And to set the record straight on that last sentence, no, yours truly was not a consultant. That notwithstanding, I’ll own up to that “he probably invested considerable emotion regarding the ultimate recreation of LA” part. I mean, they’d announced their “perfect recreation” in September of ’06. And considerable emotion had already been invested in the Chitwood case and now we’re honored to have gamers discover it here. Or take Eugene White: close to my heart, a non-criminal whose story included his wife to the detriment of his progeny””R*/Bondi later decided, in true noir form, to change White to Black…and lest we forget the O’Connor Electroplating Explosion, which I’m off to inundate myself with now…like sand through the hourglass, these are the kills of our lives. Should have you know I’m not the only one with my ear pressed close to the beating heart of 1947 and her legacy.

Historical knowledge will always at best be an approximation of the past. I know that. Clio alone possesses the real truth, and she will only allow us a glimpse of her treasure. The WPA maps, the Spence Air Photos, the 180,000 photos Bondi surveyed (ok, I raise an eyebrow at that number) show the dedication to which they aspired. It’s refreshing, since kids today seem to be under the spell of Antoine Roquentin or the influence of Paul Valéry. History may be an argument without end, granted; but history is no less potent than our present, and when it is skewed, so skewed is our present.

Thus go the criticisms of 47PplaysLANoire, they are many and varied, but at least they all recognize what I strove to point out: I’m no gamer.

Even that concept gets called to the carpet. Was lunching the other day with a pal, and the subject of my virgin PS3 came up, and I ran through my Luddite rap, blah dee blah, which at this point I admit now sounds like so much shtick.

Politely ignoring me, my friend asked “How are you of all people not a gamer?”

“How do you mean?”

“You”™re always going on about the zombie apocalypse”””

“Forthcoming zombie apocalypse,” I corrected.

“Whatever. You”™ve worked through a hundred ways to defeat zombies. Then there”™s your contingency plan for alien incursion or if the city is overrun by spies. Or Nazis. Or robots. You”™re a dedicated firearm enthusiast, and on entering a room you take stock of its exits and supplies. Didn”™t you once say that on entering a room you rank it on whom you can leave behind, but you”™d never leave behind ammo?”

“That”™s just common sense. You gonna finish your fries?”

“Not to mention that thing you do where you sit motionless staring at a screen, tapping away, for days on end. Classic gamer action.”

“Whose clinical name is hyperfocus. Blessing and a curse. Tell your gamer friends it”™s playing havoc with their dopamine levels.”

Most men memorize NBA stats, and do so in the hope they’ll get to use them: bar bet-winning material. But zombie killing tactics and SERE training is akin to having that gun in the nightstand””it’s there with the hope that it never, ever provides utility. Relatedly, why would I devote my days immersed in some blood-drenched environment, a titanic flatscreen taking me through that world I so desperately wish to avoid? I have enough problems with my nightmares. I don”™t even set foot into my local market any more because I”™m certain Y’golonac is the manager there.

But I can’t turn a blind eye to LA Noire. The concept is too engrossing, my need too enveloping. I wrote in my previous piece of the game’s relationship to historiography. At this point, in a fever to amble into 1947, any further writing on the subject would more be akin to hagiography. After which the aforementioned “painful” epithet would be hurled with deserved, less subjective abandon.

So tomorrow begins. I know it will be a succulent adventure, thick with wonder; at its best, I know it will be an interesting/painful journey.

That’s all I ever asked.

Day One: The Arrival

1947project plays LA Noire

Greetings, 47fans!

Been three years since our last post here, five-plus since those of the 1947 variety in particular. Of course post-47project there’s been On Bunker Hill and In SRO Land and many other adventures. But now it’s back to 1947–and why revisit that storied year of LA noir? LA Noire.

Unless you’ve been under a rock (a vaunted haunt, I’d say) you’ve likely heard of LA Noire. If not, here’s the skinny. Rockstar Games (renowned for their Grand Theft Auto franchise, say) and game developer Team Bondi announce in September ’06 that they intend to produce a video game set in the Los Angeles of 1947. Gamers drool over the prospective enormous open-world aspect and its MotionScan technology; we Old LA geeks get all excited about, of course, the prospect of shelving our Beta cassettes of The Turning Point and Hollow Triumph and taking a dérive through re-created 1947 LA. From there, we waited.

The years rolled on, drop dates came and went, but then, these things take time. Four years and change after that initial announcement, R*/Bondi announce Noire’s in-store buy-em-up day: May 17, 2011. In the swell of excitement and promotion before the game’s explosion onto the scene, the good folk of the gaming world go and call up those other mid-aught plumbers of the ’47geist: us.

In short, I’ve played it.

Last Saturday, Richard Schave, Kim Cooper and I were led from the Roosevelt Hotel’s sun-and-skin drenched poolside

up into one of its dark, curtain-pulled rooms. Said room’s only salient feature? 60″ flat screen. Pleasantries are made all around and we get down to the business of playing LA Noire.

They had a lot of people there to play that day, in heavy rotation. Mostly gamers from fansites, whom I’m sure picked apart the roguelike procedural sandbox algorithms, about which I confess to know nothing. (Did play ToeJam & Earl in Panic on Funkotron all the way through in 1993 and said Ok, I’ve done that. Went boating once, too, and again, figured once was enough.) Kim’s no gamer either. So we abjured the gameplay and I therefore can comment neither on LA Noire’s authority as a “game” nor on how it succeeds in its mimetic vs. diegetic structure. I was there to look at stuff. Their company rep in our room gave us a half-hour (which we stretched into an hour) to tool around Old LA — an hour of incessant mumbles and rants that surely came off as so much demented logorrhea.

All of which I’ll share with you now. Will endeavor to imbue it with some measure of coherence one notch above logorrhea; can’t guarantee it won’t be demented.

First thing I did was study LAN‘s greater map. It’s an oblong affair, kind of a boomerang shape, roughly bordered by Franklin on the north, the river at the east, Olympic along the south, and La Brea at the west. Within these boundaries there are, I was told, eight miles of perfectly rendered roads to traverse. And I fully intended to put this topography to test in the limited time I had.

So we jumped into the world. Commenced inside Central Police Division, the 1896 “Old Central” at the SW corner of First and Hill (demolished in 1956, a year after Parker Center opened, natch). There was some ambient gametalk about how I was one Cole Phelps, former Marine and newly-minted LAPD detective, which was all fine and good when, as I ambled down some hallway, I glanced out of the side of my Phelpsian eye the view through the window and espied a great dusty promontory.

Oh, I knew it well all right. It loomed over First; the Hill Street Tunnel bored through it. That the game designers could get something that correct through some random dirty window, well, that bode well.

Above, aforementioned “dusty promontory” as seen from its dust down toward the police station of which I spake. Lobby card from Shockproof, 1949, author’s collection

That hill is long gone, and I wanted to see it: without a thought I roughly pushed past the odd dirty desk and water cooler, shoving aside my fellow officer until at once, after a lifetime of waiting, I bolted out into the daylight. The 1947 daylight. Blinked my eyes in wonder. A red car trolley clattered past. Turned and peered down First at Austin’s State Building looming in the distance. I’m not ashamed to say I found the moment absolutely thrilling.

Ran into the street, badged some broad in a shiny new Hudson, commandeered her car and set off for Bunker Hill, every synapse firing. Some semaphore dared raise its “stop” signal at me and I blew through the intersection, neatly clipping a Caddy, fishtailing onto the sidewalk, sending pedestrians scurrying. (All at once I could see the appeal of this thing.) But my car, and neurons, came to a screeching halt as I hit Second and Hill — for there, instead of roadbed running up to Olive, were only stairs alongside the tunnel.

Which was just…wrong. I gunned my Hudson up those steps anyway, made it about halfway before my transport chugged to a sad stop. Fine, I’d take in the Hill on foot. I ran up the rest of the staircase (without expending any actual energy or effort…doubling the appeal!) and turned to ask…where was the Astoria? This game’s early promise was dwindlling rapidly. The Hillcrest had a butcher instead of its dry cleaners? This was not boding well.

The most-used phrase to describe LA Noire is “perfectly recreated.” Now, let me say that I’m not trying to be needlessly critical, but this is criticism after all, and it’s the only kind of criticism I do. A post such as this merely underscores that we at 1947p take our re-presentation of a world dear to our hearts with unyielding gravity. To put it nicely, omission of oft-photographed (disinclude Angels Flight Pharmacy? Really?) buildings is a bit perplexing. That the repetition of perplexing omissions was disheartening and maddening I trust is a given.

I queried some of the game guys afterward about why some landmarks might be missing, and they posited that it could be because Corporate couldn’t secure the rights to images of those structures. A possibility, but not a probability. For example, back in Noire‘s LA, I cruised up Third to Grand. Looking north, at the NW corner, there stood 301/303 S Grand, AKA 725 W 3rd. Shots of this house are pretty rare. But across the street at the NE corner, there was no Nugent, nor, at the SE corner, was there the Lovejoy, which have both been captured to great degree. Thus it was with some trepidation I walked up to Bunker Hill Avenue — which wasn’t there. It had been reconfigured as an alleyway. Bunker Hill Avenue is unusually, unreasonably important to Los Angeles, mid-Century especially; noir pictures were shot there, for example, The Castle was used in Kiss Me Deadly. If they’d asked me for any or all of my many rights-free vintage postcards of the Melrose, or unpublished kodachromes of the Castle, they coulda had ’em. (Don’t even get me started on where they put the terminus of the Third Street tunnel.)

So I trudged back to town. At least I could ride Angels Flight down to Hill, right? Nope, in this world Angels Flight is stationary. I can plow a beautifully rendered Packard Deluxe Clipper 8 Club Sedan through three blocks of streetlights, but can’t ride the arguably most iconic piece of Angelenic transportation 315 feet? With streets replete with DeSotos and crisscrossing streetcars, 1947 the height of its ridership, Angels Flight sits as motionless as it did during its down days. This too I brought up to one of the reps, and was told that what I was playing wasn’t the final version, and that perhaps a running funicular was to be, but just, you know, not in this “build.” I believe what he was attempting to connote was that I was playing an old version. So there’s your caveat, dear reader: perhaps everything I’m saying is based on some outdated model. Perhaps everything I’m bitching about is being fixed right now.

Naturally my most stringent criticism was going to be reserved for Bunker Hill; ironically, it was Bunker Hill which let down the most.

Once I was back in Noire’s downtown, my spirits lifted a bit. “Go to the Westminster!” chimed Kim, and I hotfoot-ed it down to Fourth and Main, and damned if that didn’t restore the thrilling feeling I had at the start. I took in the pre-extruded metal facade at Cliftons (now being returned to its pre-1962 visage) and was tickled by the tiki torches blazing in the doorway of the beautifully rendered Clifton’s Pacific Seas on Olive. Ambled amongst the palms toward the famous fountain in Pershing Square. The Rosslyn Hotel had her twin blade signs, just as she should. Standing at Sixth and Fig with the Gates over my left shoulder and the Richfield looming up above me was…something. The JESUS SAVES neon signs were where they should be, living large behind the library, and the Engstrum…the Engstrum. There I stood in front of the Sunkist and Engstrum with the Edison at my right. It was quite a moment. (Added bonus for the novitiate: backs to the library, a pop-up allowed us to access historical information about said Goodhue structure. These pop-uppy whatnots, suggested but not demanded, occur at the usual suspects across the City.) As an oil man by trade, my reigning interest was in motoring down to the gas holders the other side of Union Station. Those behemoths made my heart skip a beat. From there I sauntered like a flâneur up Seventh — Dodd and Richards row, pretty nice.

But it was the Spring Arcade…that really showed me the true virtue of the game. I was busy crashing Chryslers, gazing gape-mouthed as I pummeled pedestrians, blah dee blah, video game stuff, when I screeeee parked my car lengthwise across Broadway. Exited said car, walked with dedicated purpose across the street — traffic came to a halt, ladies in veils waved their begloved fists at me — and I stepped into the quietude of the Spring Arcade. It was a revelation. Deep into our maniacal race to experience all we could see in this recreated world, I was now in the Arcade sans crap electronics and discount socks: a place of peace and elegance, as anathematic to 1947 as it is to 2011. People of 2011 (that’s you) can and should traverse what is LA’s most sublime space. That you may imagine its former glory, courtesy of and via this game, is rather lovely.

Would that it were all hearts and rainbows, though. There were problems:

The Westminster lacked its trademark sunburst canopies. And consider the San Carlos: in the Noire version of ’47 reality, the San Carlos exists, structurally, somewhere between its original “wedding cake” incarnation of 1911 and its 1930s cleanlining, i.e., there was an apparent misalignment in the matter transporter integrator/disentgrator device (shameless plug for the ’58 version of The Fly) because here the San Carlos retains its Auditorium-era finials, though in a mutated streamline version. Weird.

Also, the Hippodrome has been depicted as a structure separate from the Westminster. Across the street was of course The Follies, which has here been mistakenly represented as a motion-picture house, instead of as a burlesque-eteria: its bump-n-grind 1947 reality would have actually made this landscape more noir. (I might add that in Noire’s world LA’s picture-houses, according to their maquees, featured the same few 1947 noir films, and ignored the dictate of Warner’s showing Warners, RKO showing theirs, etc.)

Where was the Follies’ neighbor Goodfellow’s Grotto, touchstone of the time? And, to this day, along the backside of the Barclay, there exists a magnificent ghost sign, sad to see the gamefolk didn’t record it — the IN Van Nuys hotel had become the Barclay a full decade before 1947: so, where was the thing? It’s not like Team Bondi wasn’t there to photographic it: we all followed the tale of their rummaging through the hotel. The Chocolate Shop was an empty lot. The Baltimore Hotel was missing its blade signage (crimininally dumpstered a decade ago), but, most shockingly, King Eddie was utterly absent. (Which is absolutely mystifying in that it stands there to this day in all its glory. Perhaps it’s just not in this “build?”) The Monarch was also plucked from the landscape. Odd.

Some examples. Here‘s a screengrab from their site.

We’re looking up Fourth toward Olive. Now, while you’re playing the game, you’re very likely concerned with that guy shooting at you. But here, we treat background as foreground, so: the designers used an early image on which to render this scene. By 1947, the Hotel Clark Garage, right, had become the Center Garage. That mission-style building, background left, the Fremont Hotel, had a blade sign running down its east flank.

Now here’s an instance where the designers used an image later than 1947 to design Noire:

We’re careening up Fig, and in the distance, the Architects Building, but see those letters atop? They read “Douglas Oil” and weren’t placed there until after Douglas purchased the building in 1959. Guess you should probably be more worried about the big scary car crashing into you, and all the flying sparks, but, well, we each have our own issues.

Again, there may be some bugs to be worked out. How was it that on my way up Main, St. Vibiana’s was missing, but turn around and head south, and it appears? The same wonkiness held true with a trip down Fig, wherein the Architects Building is an empty lot; but, motor a couple blocks and crane your head around, there it is behind you. Perhaps these li’l bugaboos (I’m sure they just rasterized their RAM with too little ROM, or something) will’ve been worked out by the time they ship product. I hope so — these bits of motorized strangeness disorient and dislodge one from the moment.

You’d think we were done for the day, but KC & I, feverishly sweating blood, handing the controller to one another, and scaring our handler with the aforementioned glossolalia, had places to go. We tore down Wilshire — as much as I love the 60s Corporate Brutalism of DMJM’s American Cement, its absence certainly put me squarely in the game’s frame. But even with the Gaylord in the distance, Wilshire petered out before we hit The Ambassador. Yes, our first instance where we had come to The End of Our World. I don’t play games; I drive around LA. So I don’t take roadblocks lightly. But I was at the mercy of a higher power. Not the AA kind. The Thirteenth Floor kind.

So as I so often do (especially when confronted with a higher power), I went another way. Up Kenmore, or Arlington (another problem with this game — no street signs, not a one — should you want to know where you are, you have to jump out of gameplay and into a map) and into Hollywoodland. I could give just as detailed a description of Hollywood as I did for downtown (to which I did a disservice by not seeing a tenth of what I intended to) but I’ll save that, I think. Something tells me this won’t be the last of this nitpickery. Suffice it to say, for the time being, seeing Sardi’s in the flesh, so to speak, was charming. That I went to bed that night replaying how I clipped a Chrysler Airflow and slammed my midnight blue ’47 Lincoln Continental convertible into the NBC building…priceless. On the other hand, one of my mussitations while motoring along Sunset was “If the globe on Crossroads is spinning the right way, I’ll buy this thing.” Not only not the right way, but not spinning. At all. Like Angels Flight, it was stationary. And did I mention it wasn’t a globe? Just a blue ball.

How apt.

And thusly we were done. I tossed the controller to the floor and breathed a bit.

Ushered back out poolside, where all was well-lit, well-oiled and eumorphous. I wanted to cry, Don’t you know where you are? But I guess what I really meant was Don’t you know where I’ve been? Richard drove us back to Lincoln Heights. I was in an impatient state of anxiety over his unwillingness to blow through intersections and use sidewalks as his motorway.

As we drove home, the streets were uncrowded, the sky was sunny. Just as it was in…LA Noire. Which raises the question — what? Los Angeles was famously congested in 1947. Moreover, 1947 LA was poisonously polluted. My synapses sprang back to life, whence came new questions: having only traversed the Noire landscape in daylight, what does nighttime look like? (Are the animated signs animated, e.g., the bowling neon on Vine or the bowling incandescent on Sunset? Do vespertine activities shift in form and function?) Is the Noire world racially accurate? (As I drive down Central to bop with the heads, how do the demographics shift? Or up Broadway into New Chinatown? If faces are actually Asian there, will they differentiate in any way from those in our ShÅ-tÅkyÅ?)

We wound through the streets. I closed my eyes and tried to keep close to 1947 LA. Traffic roared by, but it didn’t sound quite correct. I mean, a Pontiac Streamliner 8 sounds like nothing else in the world. So my final muttering of the day was vedremo. Vedremo. Those Germans, they may have a word for everything, but the Italians, they only have words for those things that absolutely matter. A favorite of theirs, heard across pre-unification “Italy,” was/is vedremo. It means we shall see. We shall see, indeed.

But I live now. It’s been a couple days and I’ve cogitated a spell. If you’ve read this far, it won’t shock you to hear that I don’t cotton to anachronism. But Mr. Nathan, I hear you say, Renaissance art was the rebirth of antiquity, but you nevertheless routinely witness The Virgin in 15th c. Italian dress and the Four Fathers in Flemmish garb all the time. I would counter that the renovatio was about the remaking of a living culture through the interjection of Greco-Roman concepts of perfection, and if you want to continue your argument, I know, town clocks didn’t strike in the ancient Rome of Shakespeare’s Julius Ceasar either. Anachronism in the commission of art, is not only nothing new, but is common currency.

But I’m not writing about those. I’m writing about this. It purports to be historical, and when that happens, I’m on the case. I’m Cole-Fucking-Phelps.

Thus I am a detective, present day, but with retrocognitive disorder. Retrocognition is the concept that one can view a place and see into it its variegated layers of the past. While I may appear flippant on the subject, trust me, it’s a difficult state of perception to harbor or describe. The German critic Walter Benjamin described the colportage phenomenon of space, wherein “we simultaneously perceive all the events which might conceivably have taken place here.” But I don’t see Los Angeles, historically, as collapsed space; I see it as an artichoke, where one must peel back layers to reveal its heart. But it’s also an onion. Peel away its layers, find nothing inside, end up crying.

Neither 1947 Los Angeles nor its progeny LA Noire merely exist within the colportage; this game is being entered into the historiography of postwar Los Angeles. That canon is unbearably important (you know, to some of us), but who are its keepers? From March 2005 on, there was us at 47p. As has been discussed on this site, Ask the Dust didn’t look quite right, and DePalma’s 1947-fest Black Dahlia, released the year LA Noire was announced, shot as it was in Bulgaria, didn’t look quite right either. Those two movies were of course seen by a sum total of eleven people. Of HBO’s recent Mildred Pierce — tossing in a handful of palm trees and some awkward CGI couldn’t change the quality of that New York light. MP was seen by about a million people. Rockstar’s most recent venture, Grand Theft Auto IV, has sold twenty million units.

Noire shall then be the introduction for many to the wonderful world of 1947 Los Angeles, and as they learn it in its eidetic state, they are going to come away with a view of the City at a place in time that is almost, but not quite. If they learn it here first, then, when they subsequently see it presented accurately, they’ll figure the simulacrum to be the true version. (If this paragraph incites just one discussion about teleology and metanarrative, that would be awesome. If it makes you think about the Bath Block, that would be better.)

Coleridge was all up in our grill about willingly suspending disbelief. As such, I’d like to think the onus was solely on me, infinitely forgiving the game designers, and overlooking the limitations of the media — but I can’t. I understand that when I watch Life On Mars, set in the 70s, it’s low budget; they can’t remove every incorrect park bench and satellite antenna. That the Coens couldn’t expunge some modern Carl’s Jr. signage from their set-in-1980 No Country for Old Men, well, fine…their budget was a mere twenty-five million dollars. But LA Noire is total fantasy, drawn (literally) (no, not literally, because they “capture” these things, but anyway) from images, and its budget is fifty, maybe a hundred million dollars. So forgive me should I seem to hold these gents to unreasonably high standards. In layman’s terms, I’m not sayin’, I’m just sayin’: the past has as its nature an irretrievability and should someone attempt to articulate it, they are opening themselves up to rearticulation.

To wit: I think there’s a certain Whiggishness at work here, and rightfully so. LA of Noire is portrayed in all the glory of its expanse, after all, 1940s LA affluence and vastness took countless untolds out of the slums of the East. Its portrayal here is at the same time a revisionist history, in that LA’s skies are rendered blue and her streets rasterized as nearly empty. I have not, of course, touched on the whole “1947 LA is thick with serial killers and corruption” history, because I did not technically play the game. From perusing the R* site, seems like they’ve an angle as regards the Jeanne French killing. As “crime buff” falls under the umbrella of social historian, I have come to know, and from there have become close to, Jeanne French. Not Ellroy/Short close, but, still, don’t like to see her memory played with. The women for whom I have a particular affinity — Trelstad and Mondragon and of course my comrade Evelyn Winters — how, if at all, will they be fictionalized in this game?

Obviously, I want the world of 1947 treated with some respect. Noire’s designers did a commendable job, and were not lazy in attempting to achieve great things. But let me have a parting shot at this “perfectly recreated” business — the pundits routinely repeat it. I expect lazy journalism. But let’s say 1947 LA was perfectly recreated. By whom? Obviously not by someone with phenomenological understanding of the time and place (though such folk do exist, they are now really rather unreliable, God bless ’em) so it must therefore be done by historians…many of whom I know, none I which were ever contacted. Personally, I’ve never been to the past, nor have the game’s designers or builders, or scripters. Therefore LA Noire has an enormous burden to bear regarding its legacy — and if they’d worked on it another five years, would they reach a level of accuracy that would be acceptable to me? Even if I gave it an A-1 rating, wouldn’t some upstart still pick it apart?

Noire, I’m assuming, will be an international success. The upside being it will introduce the public to a world they may have never considered: e.g., one without computers and cell phones. Will players perceive this as a pro or con? How and why might they reinterpret their present via time spent in the past? We may romanticize the past, but nothing’s sugar-coated in noir. Murder is one thing; it’s eternal. 1947’s specific relationship to race and gender and class is something else altogether, and what players take away from living in that world, for however short a spell, will be telling. Heck, would it be cooler to play the game wth a case of typhoid or TB? One can only hope the millions who navigate this new (old) world take from it something useful and interesting. (Maybe they’ll even go and investigate some old noir thereby freeing up a seat for a good movie.)

But here’s the thing. I teach people the past. And now, along comes the best flight simulator I’ve ever seen. So is it better that LA Noire exists in its imperfect form than to not exist at all? I suppose so, since, as a young man it was beat into me that the cacotechny was part of the flux of art. And yet one can argue that producing something this good, this complex, with such problems, should not have been done. It raises too many philosophical issues, none of which I’m prepared to discuss, and likewise too many architectural issues, all of which I’m hot to discuss.

Which, unfortunately for both of us, dear reader, I will now have to do. As in, I just totally Amazon’d a PS3 (whatever that may be) and a 60″ flatscreen, just like they had in that there Roosevelt hotel room. And I have the sneaking suspicion that I’m going to spend the majority of these forthcoming lovely spring days, when a boy’s heart turns to romance, holed up in my TV room, shooting people in the face and driving an Olds up those Second Street stairs, whether they existed in real life or not.

It begins.

__

Reserve to take Nathan Marsak’s free downtown L.A. Noire walking tour on May 29. Details here.