Los Angeles

In one Memorial Day observance, Col. James H. Davidson of Pasadena addresses the crowd at Memorial Hall.

He says, in part:

May 30, 1907

Los Angeles

Call me an embittered divorcée—male though I may be—but it seems I can’t get enough of any tale involving marital disharmony (cf. May 25, or more saliently, May 17). Those in the thrall of wedded bliss, or, more likely, righteous pique, tut-tut our modern divorce rate. Well…

Old soldier Alonzo Stuart, 70, met Ida, 38, at a Sawtelle church. She spoke to him without an introduction (!) and during said discussion he revealed he owned an acre down on Fourth Street. They took a stroll to go look at the property, whereafter she promised to be a good and loving wife. He deeded her the acre. We know where this is going.

A good and loving wife she was not, as was evident on the very day of their marriage. While eating iced cream in Eastlake Park, the elder Stuart laid his arm affectionately across the shoulder of his new bride, but she moved her chair away, saying she did not care to be slobbered over. Stuart pal Frank Conckling recounts further tales of newlywedded smoochiness, including this one, after his visit to the Stuart’s Sawtelle home on Sixth: “She was sitting outside reading a murder story from a sensational paper. I asked her where Stuart was, and she said: ‘He’s inside cleaning up his dirt.’ I went in and found him down on his knees, scrubbing the floor.” Ida also reportedly stated to her husband that she was not going to be dictated to “by any damn man.”

At the trial, Alonzo admitted to being, at times, remorse and sullen, but only because his heart was grieving. And yes, he did brandish a pistol, but was calm and quiet and in fact perfectly good natured while doing so.

Ida recounted that they argued frequently—for example, she wished to go to the beach without him. “The last fuss we had was over religion,” she said. “There are so many different kinds of religion in Sawtelle.”

The value of the disputed property is $1,400.

May 27, 2007

Los Angeles

It is more than two weeks now since the graders came and removed the surface layer of the asphalt on Avenue 20, between Albion and Broadway, then went away without finishing their work. For all that time, the NO PARKING signs have hung on the telephone poles, and the regular parade of shortcutting commuters have bounced along on their unhappy shocks, as the street beneath them grew more uneven and dilapidated.

After a week, a flash of red edged by corroded silver was visible on Avenue 20 just before Broadway. A careful peek between passing cars revealed a long-buried light rail track, with a row of handsome, narrow brick placed alongside it.

For this neglected area, just NE of downtown on the far side of the river, was once a thriving commercial and residential community, with trains running frequently down the middle of the streets.

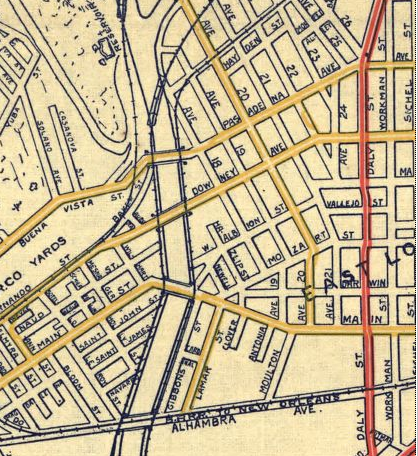

Here is a map of the immediate vicinity, drawn in 1906. The yellow lines demark the Yellow Trains of the Los Angeles Railway Company, and just in the middle heading approximately north-south you’ll find the line that ran along Avenue 20, passing between Main Street and Downey, now known as Broadway. Behind the dead end at Main, the Los Angeles Brewing Company, now the Brewery Arts Complex. Avenues 21 and 22 are ghost streets, their rows of Victorian cottages bulldozed so the 5 can whisk folks away at speeds unimaginable in ’06. Mayden too is no more. And the red line along Daly is a Pacific Electric Railway Company train.

Back to the state of the very sad street. Well into the second week with the gravel laid bare to constant steamrolling by SUVs and minivans, new patches opened up closer to Albion Street. Viewed from behind the windshield, these had a strangely archaic quality that demanded further inquiry.

Here is the intersection, with the peculiar patch visible in situ. You can see how dangerous it is to get close to the quarry:

But your intrepid reporter would not be daunted in her quest to see if that was really what it appeared to be. Wait for it… wait and… wait and… dash out and take a snap!

Aaaaahhh! Yes, those truly are cobblestones, that timeworn weapon of the disenfranchised European citizenry, laid alongside the old tracks in the heart of 21st Century Los Angeles. And somewhat haphazardly mortered, too. How extraordinary!

City of L.A., your street services suck, but I can’t really be angry that you scraped up my block and disappeared, because the sight of long-covered cobblestones have a peculiar calming effect on history geeks. So thanks a million for the cool experience. I’ll never look at the street the same way again. Now will you please get some guys over here to pave the freaking street?

your pal,

Kim

Stationery engineer Samuel E. Moss, of 704 East Fifth Street, is still strapped to a bed in Receiving Hospital today, having been arrested in Westlake Park the night of the 21st after attempting suicide with an overdose of bromide.

It seems Mr. Moss, who has no apparent motive for the act (“He is a magnificent specimen of manhood and that he should so fondly court death seemed peculiar to the police,” the Times informs), was thwarted by a crafty druggist. Druggists have come under State Board of Pharmacy scrutiny of late–usually because they’ll sell opium to any and everyone–and so when Moss asked for a “big dose of carbolic”, the pharmacist slipped him the bromide.

In Westlake Park, Moss gulped down the bromide, which made him sick and semiconscious; he was picked up by a Westlake Park Special Officer.

Every morning since his induction to Receiving, attendants ask Moss if he wants to live. And every morning he says no, which confounds Chief Surgeon Garrett. “He is one of the most remarkable prisoners I have ever known. Ninety-nine people out of a hundred who try to commit suicide do so in a fit of despondency. When they are saved, they are only too glad to be alive. This man seems as strong in his desire for death now as he did when he took the drug and restraint seems about the only remedy for him.”

Questioning his Fifth Street rooming house cohabitators revealed nothing. Moss acts and speaks rationally, merely stating “If I don’t want to live, that’s no one’s business but my own.” And so his morning questioning continues–and if he continues to answer in the negative, Garrett will have no other recourse but to file a complaint with the State Board of Insanity Commissioners.

Mr. and Mrs. Simon Condon are building a home on the corner of Long Beach Boulevard and Sixty-First Street, an activity oft interrupted by Simon’s destructive rampages. It would seem that Mrs. Condon holds the family purse-strings, which Mr. Condon deems unfair (and objects to strongly) in that the house-building money came from a $1,000 injury settlement, the result of his meat-packing accident at the Simon Maier Packing Company.

Mr. and Mrs. Simon Condon are building a home on the corner of Long Beach Boulevard and Sixty-First Street, an activity oft interrupted by Simon’s destructive rampages. It would seem that Mrs. Condon holds the family purse-strings, which Mr. Condon deems unfair (and objects to strongly) in that the house-building money came from a $1,000 injury settlement, the result of his meat-packing accident at the Simon Maier Packing Company.

And so Simon attempted to murder his wife with a scythe, whereafter Mrs. Condon had no recourse but to call the local constable. Simon stated to the officer that he will indeed succeed in killing her if he doesn’t get the money.

Jailhouse investigation reveals Mr. Condon to be neither intoxicated nor insane.

May 25, 1907

Los Angeles

For eleven years, pigeons have filled the nooks and roosts of the city’s police station, watching over the parade of troubled souls who come to that refuge, some dragged in bodily, others seeking aid. The police officers have coddled their feathered confederates, keeping them fat with daily offerings and giving names to the most distinctive of their numbers.

All that ends tomorrow, by order of the city’s judges and police officials. They have determined that the impromptu coop is a filthy nuisance and a hotbed of avian vice, and with that stark declaration, these spoiled creatures have been sentenced to death by sniper.

Yes, they will all be shot–starting with Old Bill, the big black male who reigns over his flock, and followed by all his courtiers, wives, children and cousins. Once their fate became clear, the officers insisted guns must be used, for they could not bear to snare and strangle their friends, and if they trapped and shipped them away, it would only be a matter of days before they returned to their longtime home.

Tonight the police station is a mournful place, and the sweet cooing of its aerial residents inspire only sadness in those below. Old Bill has but one night to live, and when he dies so too will a piece of the hearts of all who knew him.