On April 10, 1940–seventy-two years ago today–a man named Edmund M. Hart walked the streets of Medford, Massachusetts in the county of Middlesex, knocking on doors and making inquiries about the people who lived behind them. He was the designated U.S. Census enumerator, and the personal information he gathered has just this month been placed online.

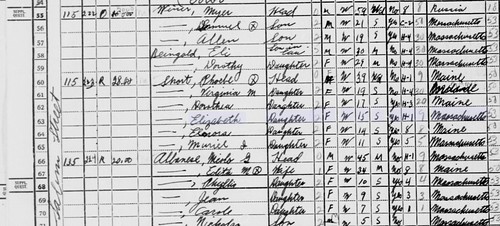

On Salem Street, at number 115, Hart recorded the particulars of three separate households.

The owner of the property (valued at $5000) was Myer Winer, aged 59. A widower, he lived with his sons Samuel (21) and Allen (19), his daughter Dorothy (29) and her husband Eli Reingold (30). The young people were all born in Massachusetts, Myer Winer in Russia. He was a tailor in a retail clothing store, earning $700 for the previous year (for only 18 weeks work). Son-in-law Eli Reingold was employed as a clerk in a wholesale tea company, earning $1200 for the previous year (52 weeks). His wife, a stenographer for the Commonwealth of Massachusetts, earned the same wage for her 52 weeks of work. Although the census did not ask, we know from other sources that theirs was a Jewish family.

Paying $35 in monthly rent was Edwin F. Jones, 58, and his wife Minnie, 56. He was from Maine, she from Massachusetts, and both had been living in the same house for at least five years. Jones was a newspaper printer, with wages of $2350 for the previous year (47 weeks work).

It is the third and final family which draws our attention, for reasons having nothing to do with their quiet life in Medford, Mass. The head of the household is Phoebe Short, 39, native of Maine. She tells Mr. Hart that her family of six has been living in this place for at least five years, and pays $28 rent–$7 less than Mr. and Mrs. Jones, perhaps a reflection of Myer Winer’s charity. Although unemployed, she has an unspecified income of more than $50, not from wages. This is, we assume, money provided to her by her estranged husband Cleo.

Living with Phoebe are five unmarried daughters. Virginia M. (19), is the only one seeking work outside the home, claiming 34 weeks unemployment through the end of March 1940. Her occupation is given as New Worker, meaning she had left school but had not yet secured any position. The other Short sisters are all in school: Dorothea (17), Elizabeth (15), Elenora (14) and Muriel J. (11).

Although history records that Phoebe Short’s husband Cleo was still living, she identifies herself to the census as a widow. Maybe at this time, Phoebe really thought her husband was dead. Maybe she claimed to be a widow instead of admitting to a stranger that she had been abandoned. We do not know if the story she told Edmund Hart was the same one that she told her landlord and her daughters. The bare facts of the census record cannot reveal the nuances of any family’s tragedy.

Phoebe’s pretty daughter Elizabeth (15) is frozen in time by the census keeper’s ink. She is still safe with the women who know and love her, still free to walk out the front door on a balmy day and turn west on the Salem Road, which is will not for some years be bisected by I-93, a highway which seems to have obliterated 115 Salem Street. Half a mile from her home, past the movie theater and the city hall, is the old Salem Street Burying Ground, a neglected cemetery dating to the late 17th century. Maybe she wandered there, among the winged skull markers and crumbling walls, and thought about her own mortality and imagined the joys her life would contain before the grave.

She’s still a couple of years away from her ill-considered escape from the limited opportunities available to a poor, fatherless girl in the Boston suburbs. When she runs, she will go to California, to be reunited with Cleo Short. Their relationship will quickly fracture, and she will become a vagabond, moving often and forming short-lived, intimate relationships with strangers. She will travel from California to Florida, to Chicago, then west again. She will lie to her mother, and she will not look for work. She will sink into depressive obsession over a promising relationship cut off when the man dies in a plane crash. She’ll make some foolish choices, and some stupid ones.

And at 22, they will find her body cut into two pieces, naked and brutalized, in a vacant lot in Los Angeles. She will find posthumous fame as the beautiful victim of one of the most heinous unsolved crimes in American history. They will call her The Black Dahlia, leer over the terrible photographs, and they’ll never stop talking about her.

But for this moment, she is still frozen in time. The census taker knocks on the door, and wants to know: who is the head of this household? What are the names of the children, and their ages?

Elizabeth Short is 15 years old, and it is springtime. The possibilities are limitless. And we are far away, and remembering a girl we never knew.

Thank you, Joe Cianciarulo, for the detective work.