Los Angeles

Five years ago, Mrs. C. P. Rapp lived in bustling Sioux City, where everything was hunky-dory. Sure, there was that famous unpleasantry in 1900 with the John Pierce swindle, but that

Five years ago, Mrs. C. P. Rapp lived in bustling Sioux City, where everything was hunky-dory. Sure, there was that famous unpleasantry in 1900 with the John Pierce swindle, but that

John Sheres has graced Los Angeles with his presence. The professional adventurer, or, as he self-describes, “chronic loafer,” boasts that he has never done a month’s of real work in his life. Sheres says he has been a wanderer ever since he was able to walk, and as such was promptly arrested and given a short jail term on his arrival in our Fair City.

Town to town, jail to jail, Sheres wanders, or “beats;” he was beating his way to San Francisco looking to jump some vessel bound for New York. He is hoping to reach England, from where he intends to finagle passage to South Africa or India.

Released to-day from our local gaol, the itch to move is upon him, and so we shall bid farewell to Mr. Sheres. We wish him a fulfilling life of beating, unburdened by the terrible specter of work. He states he expects to die a professional tramp.

More marital bliss! At six p.m. Frank Harrington, 38, was drinking in a saloon at Thirty-Eighth and Central with his buddy George Tanner. Tanner asked if Frank was feeling better, after having been under the weather of late, to which Frank merely replied “No–I feel bad.” Frank took off home, and the next thing Tanner heard were pistol reports. He dashed a short distance to the Harrington home, 3505 Central, where the Harringtons resided behind the delicatessen in which Frank and his wife Susanna tended shop. Tanner made a terrible discovery.

Frank’s brains were on the floor. Mrs. Harrington, 52, had had a bullet pass from behind her left ear, tearing away her palate on its egress; another entered behind her right eye and exited through the right side of her face, a third left a bad opening across her forehead. The coroners were called.

Coroners take their own sweet time, because, after all, what’s the rush? Their bodies therefore lay on the floor for two hours before the wagon came. One thing, though. The Harringtons were still alive.

The papers state that Harrington, at Receiving Hospital, is still alive but “liable to die at any moment.” Mrs. Harrington was removed from Receiving to Good Samaritan Hospital, where it was reported that she never lost consciousness through the ordeal.

Acquaintances note that despite the couple’s interesting age difference, Mr. Harrington was often jealous, and the two therefore quarreled routinely.

Further investigation into news accounts of the time does not reveal whether one or both of the Harringtons survived and, if they did, whether they stayed together afterward, thereby fulfilling the old “til death do us part” pledge.

May 30, 1907

Los Angeles

Call me an embittered divorcée—male though I may be—but it seems I can’t get enough of any tale involving marital disharmony (cf. May 25, or more saliently, May 17). Those in the thrall of wedded bliss, or, more likely, righteous pique, tut-tut our modern divorce rate. Well…

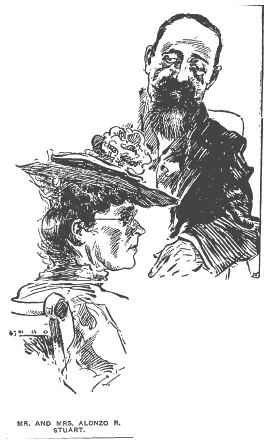

Old soldier Alonzo Stuart, 70, met Ida, 38, at a Sawtelle church. She spoke to him without an introduction (!) and during said discussion he revealed he owned an acre down on Fourth Street. They took a stroll to go look at the property, whereafter she promised to be a good and loving wife. He deeded her the acre. We know where this is going.

A good and loving wife she was not, as was evident on the very day of their marriage. While eating iced cream in Eastlake Park, the elder Stuart laid his arm affectionately across the shoulder of his new bride, but she moved her chair away, saying she did not care to be slobbered over. Stuart pal Frank Conckling recounts further tales of newlywedded smoochiness, including this one, after his visit to the Stuart’s Sawtelle home on Sixth: “She was sitting outside reading a murder story from a sensational paper. I asked her where Stuart was, and she said: ‘He’s inside cleaning up his dirt.’ I went in and found him down on his knees, scrubbing the floor.” Ida also reportedly stated to her husband that she was not going to be dictated to “by any damn man.”

At the trial, Alonzo admitted to being, at times, remorse and sullen, but only because his heart was grieving. And yes, he did brandish a pistol, but was calm and quiet and in fact perfectly good natured while doing so.

Ida recounted that they argued frequently—for example, she wished to go to the beach without him. “The last fuss we had was over religion,” she said. “There are so many different kinds of religion in Sawtelle.”

The value of the disputed property is $1,400.

Stationery engineer Samuel E. Moss, of 704 East Fifth Street, is still strapped to a bed in Receiving Hospital today, having been arrested in Westlake Park the night of the 21st after attempting suicide with an overdose of bromide.

It seems Mr. Moss, who has no apparent motive for the act (“He is a magnificent specimen of manhood and that he should so fondly court death seemed peculiar to the police,” the Times informs), was thwarted by a crafty druggist. Druggists have come under State Board of Pharmacy scrutiny of late–usually because they’ll sell opium to any and everyone–and so when Moss asked for a “big dose of carbolic”, the pharmacist slipped him the bromide.

In Westlake Park, Moss gulped down the bromide, which made him sick and semiconscious; he was picked up by a Westlake Park Special Officer.

Every morning since his induction to Receiving, attendants ask Moss if he wants to live. And every morning he says no, which confounds Chief Surgeon Garrett. “He is one of the most remarkable prisoners I have ever known. Ninety-nine people out of a hundred who try to commit suicide do so in a fit of despondency. When they are saved, they are only too glad to be alive. This man seems as strong in his desire for death now as he did when he took the drug and restraint seems about the only remedy for him.”

Questioning his Fifth Street rooming house cohabitators revealed nothing. Moss acts and speaks rationally, merely stating “If I don’t want to live, that’s no one’s business but my own.” And so his morning questioning continues–and if he continues to answer in the negative, Garrett will have no other recourse but to file a complaint with the State Board of Insanity Commissioners.

Mr. and Mrs. Simon Condon are building a home on the corner of Long Beach Boulevard and Sixty-First Street, an activity oft interrupted by Simon’s destructive rampages. It would seem that Mrs. Condon holds the family purse-strings, which Mr. Condon deems unfair (and objects to strongly) in that the house-building money came from a $1,000 injury settlement, the result of his meat-packing accident at the Simon Maier Packing Company.

Mr. and Mrs. Simon Condon are building a home on the corner of Long Beach Boulevard and Sixty-First Street, an activity oft interrupted by Simon’s destructive rampages. It would seem that Mrs. Condon holds the family purse-strings, which Mr. Condon deems unfair (and objects to strongly) in that the house-building money came from a $1,000 injury settlement, the result of his meat-packing accident at the Simon Maier Packing Company.

And so Simon attempted to murder his wife with a scythe, whereafter Mrs. Condon had no recourse but to call the local constable. Simon stated to the officer that he will indeed succeed in killing her if he doesn’t get the money.

Jailhouse investigation reveals Mr. Condon to be neither intoxicated nor insane.

John B. Metz seems like just another suicide–the 44-year-old Deputy County Assessor was a well-dressed, well-trusted official-about-town who would often brood about how he would never marry because some girl had once jilted him. So when his body was found by the landlady at 514 South Wall Street, hanging out of bed with foam on his lips, self-administered poison was thought to be the death-dealing culprit.

Or could the positioning of his corpse be signs of a struggle? And what of the various recent sums of money, now missing, not properly turned into the Assessor’s office? Yesterday, before his after-work bout of heavy drinking (including, perhaps, a carbolic of some sort) Metz failed to turn in $120 ($2,637 USD 2006) which remains missing to-day.

Metz was removed to Bresee Brothers Undertaking at 855 South Figueroa; they will perform an autopsy as to aid the inquest.

May 17, 1907

Los Angeles

1907, as now, was full of drunken suicidal maniacs in the thrall of homicidal rage. True, there are some differences now as opposed to then: opium was a lot easier to get. Divorces, less so.

H. A. Lyon, 70, met a 26-year-old Swedish girl by the name of Alva and, after knowing her a scant two weeks, married her. She went on to burn all the pictures of his first wife, and all the letters he had kept. Then Alva began to burn all of his incoming mail, especially those missives from his children; she consigned their pictures to the flames as well. Moreover, she forbade him to go to church. These troubles brought on two heart attacks which H. A. survived, and which convinced him he’d had enough.

He therefore went before Judge Monroe to confess his mistake (Alva was not present, having gone on a short trip back to Sweden and only returned to the States as far as New York).

Unfortunately for our hero, the Judge intoned from the bench: “They couldn’t live together and she left him. Apparently he was very glad to have her go, and gave her the money to take her away. A divorce cannot be granted in this case, under the law, and I’m very glad it can’t be.”

Ah, the touchstones of our time.

The Padrone must run a tight ship. Juan Acosta is a Padrone. He has a shotgun.

Just east of the city, at the Bixby Ranch, he discharged four men from one of his tents for reasons unmentioned. These gentlemen returned before daybreak and one of them, a Juan Diaz, stabbed a sleeping Acosta through the arm, and then stuck him in the breastbone and forehead. Acosta still managed to grab his shotgun and unload onto Diaz’ abdomen at point-blank range.

El Padrone’s brother managed to tackle and hogtie another assailant, one Luciano Morro, who was found bound at the entrance of the tent by local Marshals. The two others, Mssrs. Bartello and Rodriquez, now have warrants out for their arrest.

Padrone Acosta is expected to pull through. The outlook for Diaz is not as rosy.