By Norma Meyer

COPLEY NEWS SERVICE

September 15, 2006

LOS ANGELES – The most notorious body dumpsite in L.A. history is now the manicured front lawn of a post-World War II home on a quiet street lined with similar one-story stucco houses.

There’s no memorial plaque or hint this is it – the macabre magnet where, nearly 60 years ago, the Black Dahlia’s naked corpse was discarded in two cleanly cut hunks in a weed-choked vacant lot.

“She was very deliberately posed to be seen,” says crime connoisseur Kim Cooper.

The 39-year-old Angeleno lingers on the same Norton Avenue sidewalk where a stroller-pushing young mom discovered the blood-drained Dahlia, her mouth sliced on each side to form a deranged clown grin.

In Brian De Palma’s “The Black Dahlia,” this horror landmark, along with most of 1940s Los Angeles, is actually Bulgaria, where the movie was mainly shot. Noir hipsters Cooper and Nathan Marsak bring luxury buses to the real thing: This weekend they will launch the expanded Real Black Dahlia Crime Bus Tour, a doomed heebie-jeebies journey that includes Hollywood flophouses and hangouts frequented by 22-year-old cash-strapped Elizabeth Short.

It’s a cold, cold case. In that vein, bus-traveling groupies will gorge at a Hollywood gelato shop debuting 12 unique Black Dahlia flavors. One is Vanilla and Whiskey.

As it’s been said before: The Dahlia is to Los Angeles what Jack the Ripper is to London.

Massachusetts-bred Betty Short was a transient unemployed ex-waitress who hit town in mid-1946, left for a while to live in San Diego, and returned here six days before her mutilated body turned up in the Leimert Park neighborhood on the clear morning of Jan. 15, 1947.

An aspiring starlet, she was among the wannabes who flocked to a Hollywood still in its heyday. Around the time, a homegrown ingénue named Norma Jeane changed her name to Marilyn Monroe. “The Big Sleep” star Humphrey Bogart immortalized his handprints and footprints in the famous forecourt of Grauman’s Chinese Theater. The poignant classic about WWII vets, “The Best Years of Our Lives,” was about to sweep the Oscars.

And singing cowboy Gene Autry rode Champion in a parade down Hollywood Boulevard, the nightclub-dotted street that a roommate said Short often prowled.

But the social climate was changing in the City of Angels.

“A lot of women who had worked and been independent during the war were in the process of being pushed out by servicemen returning home,” says Cooper, who with Marsak and Dahlia expert Larry Harnisch deftly blog the city’s bygone murders and mayhem on the Web site project1947.com.

“There was a lot of conflict. There was also a huge housing crisis and people were forced to move in with their family and rent rooms.”

Back then, a pimento cheese sandwich cost 20 cents. A top sirloin steak dinner was $1.65. A glass of port, 17 cents. Short didn’t have much money for any of it: Friends told police she sponged off men for meals.

The flower-fond brunette – she dyed her brown hair jet-black – was last seen alive Jan. 9, 1947, in the marbled and chandeliered lobby of the downtown Biltmore Hotel. She had been dropped off by Robert Manley, a married traveling salesman who drove her up from San Diego and, along with hundreds of suspects and crazed confessors, would be cleared in the case.

Detectives, after finding two votive candles in Short’s checked bags at a nearby bus station, questioned Biltmore bathroom attendants to see if she was seen fixing her bad teeth. The Dahlia used candle wax to plug cavities.

No one knows for sure what happened to Short after she left the Biltmore. “She may have gone to the Crown Grill. Some people said they saw her there,” Marsak says. The long-gone downtown bar is now Club Galaxy – “100 Beautiful Girls,” the sign outside beckons.

Short did stay at the nearby Figueroa Hotel in September 1946, when she met a uniformed Army soldier on a street corner, according to FBI files. The serviceman said he took the “very friendly” and “very well-dressed” Short to see Tony Martin’s broadcast at the CBS studios in Hollywood, and to dinner at Tom Breneman’s restaurant, the home of a popular morning radio show. At Breneman’s, the headwaiter recognized Short and waved her through a line of waiting patrons.

The soldier said he spent the night at the hotel with Short and she mentioned “Los Angeles was a tough city and that it was dangerous for a girl to be alone on the streets at night.”

In Hollywood, Short bunked at several places until she landed at the still-standing, then $1-a-night Chancellor Apartments, where she shared a room with five women. The manager once held Short’s suitcase as collateral when she tried to skip on the rent.

In early December 1946, Short left for San Diego. Dorothy French, an usher at the downtown Aztec Theater, took pity on the sad soul she saw hanging around and invited her to stay with her family at the Bayview Terrace housing project in Pacific Beach, according to news reports. The Frenches were about to boot the jobless, partying Short when on Jan. 8 she checked into a Pacific Beach motel with Manley, whom she’d met a few weeks before. He told police they spent a platonic night together and then he drove her up to the Biltmore, ostensibly to meet her sister.

When Manley left her that evening, she was a pretty black-clad drifter who got her nickname from a Veronica Lake movie of the time, “The Blue Dahlia.” Today, the morbid icon is a cottage industry: There are Internet sites, a TV movie, a coffee-table book that connects her killing to surrealist art, and a tome that implicates Los Angeles Times publisher Norman Chandler and mobster Bugsy Siegel in her sadistic slaying.

The 1947 Project online offers Dahlia T-shirts and beer steins and a baby bib for snookums that reads, “Elizabeth Short Got A Ride to 39th & Norton – and all I got is this dumb bib.”

The Dahlia bus will drive by the site of the trash dump – several miles from the crime scene – where Short’s black shoe and patent leather purse that smelled of her perfume were found (it’s now a parking lot next to a commercial building).

And it’ll ferry by homes of men fingered as the murderer in some of the umpteen Black Dahlia books and essays. There’s the Mayan-like Hollywood mansion of venereal disease physician George Hodel, who was posthumously branded the butcherer by his former cop son; the house a block away from where the body was found that was inhabited by Walter Bayley, a now-dead surgeon whom Dahlia-whiz Harnisch theorizes did it; and the south Los Angeles ‘hood where alcoholic lowlife Jack Anderson Wilson may have drained his prey’s blood in a bathtub, according to John Gilmore, who authored “Severed: The True Story of the Black Dahlia Murder.”

Gilmore says Wilson provided details to him only the killer would know shortly before he died in a 1982 hotel room fire. But now the true-crime writer isn’t convinced the case is solved.

“It will always be one of L.A.’s darkest mysteries,” Gilmore says. Then he compares the Dahlia’s haunting legacy to the movie-star handprints and footprints she surely ogled on Hollywood Boulevard.

“It’s like Grauman’s Chinese. Her name is carved in the concrete of L.A.”

Link

She was out carousing, divorced, jobless, though with, I’d wager, a mind still keen and ticking, before she was found nearly nude, beaten, and dragged for some way, near the Ducommun Street railroad right-of-way, here:

She was out carousing, divorced, jobless, though with, I’d wager, a mind still keen and ticking, before she was found nearly nude, beaten, and dragged for some way, near the Ducommun Street railroad right-of-way, here:  Evelyn, homeless, now has a homeless encampment on her site. So, then there’s this Tiernan character.

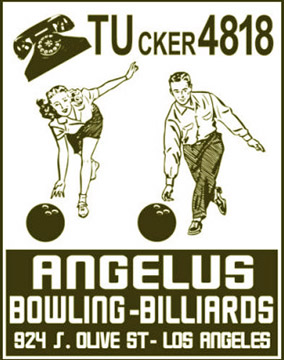

Evelyn, homeless, now has a homeless encampment on her site. So, then there’s this Tiernan character.  He’s twelve years Evelyn’s junior. A former employee of the Angelus Bowling and Billiard Recreation Center,

He’s twelve years Evelyn’s junior. A former employee of the Angelus Bowling and Billiard Recreation Center,  which is now a parking lot:

which is now a parking lot:  (for more on prewar bowling alleys, go

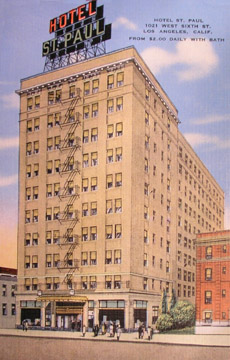

(for more on prewar bowling alleys, go  (Sanwa Bank Plaza, AC Martin, 1990) Never did find a vintage image of the Albany; some flavor of the wiped-out neighborhood–one block west:

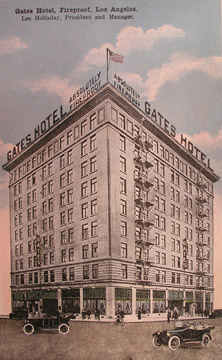

(Sanwa Bank Plaza, AC Martin, 1990) Never did find a vintage image of the Albany; some flavor of the wiped-out neighborhood–one block west:  And one block east:

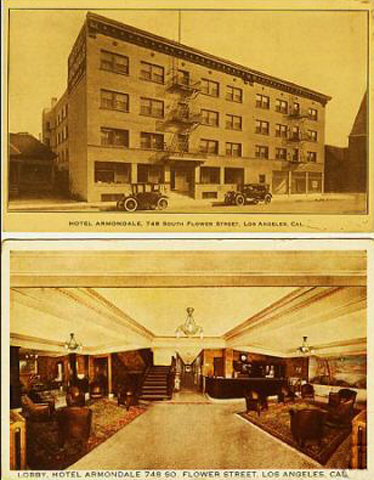

And one block east:  But why the hotel room? We don’t know. Tiernan didn’t live at the Albany. He lived at the Armondale, at 728 South Flower.

But why the hotel room? We don’t know. Tiernan didn’t live at the Albany. He lived at the Armondale, at 728 South Flower.  Its site today:

Its site today:  First off, what, already, is up with the Armondale Hotel? It has that “built on Indian burial ground” cachet that money can’t buy. Perhaps it was simply built over one of those giant magnets. The kind that attract ne’er-do-wells. The place had trouble attached from the get-go. Dale Carleton, developer and proprietor of the spanking-new 1914 Armondale, is sued by wifey Marie for a sizable share of his $250,000 net worth. Mrs. Carleton names a Ms. Helen Williams–Armondale telephone girl whose duties apparently went above and beyond the working of switchboard–as correspondent. 1919. Wilbert Garrison, 28, son of a wealthy publisher in New York, drove across country with a buddy and they holed up in the Armondale. A week later Wilbert left in his room his money, valuables, and a note indicating that he did not want to be a burden on others, and as such was ending his life. Despite the best efforts of the Nick Harris detective agency (who calls the cops in 1919), Wilbert is never found. 1930. Mrs. Louis Valenzuella, 40, ex-wife of Deputy Sheriff Valenzuella, is found dead in the Armondale of a suspected drug overdose. 1939. Washed-up boxer Louis Menney, 22, Armondale resident, is tackled by a priest after he sexually assaulted a 62 year-old woman in a church at 9th (now James M. Woods) and Green. Turns out he’d–moletsed? raped?–the papers will only mention “morals offenses”–a nine year-old in the church as well. Moreover, he’d done his business with a six year-old girl on the corner of 11th (now Chick Hearn) and Georgia, and also kidnapped and robbed an Agnes M—– and sexually assaulted a Margaret L—– in a church on West Adams; since the kidnapping charge is death penalty territory, we can only hope the Armondale’s most famous resident ended up in the proper hands.

First off, what, already, is up with the Armondale Hotel? It has that “built on Indian burial ground” cachet that money can’t buy. Perhaps it was simply built over one of those giant magnets. The kind that attract ne’er-do-wells. The place had trouble attached from the get-go. Dale Carleton, developer and proprietor of the spanking-new 1914 Armondale, is sued by wifey Marie for a sizable share of his $250,000 net worth. Mrs. Carleton names a Ms. Helen Williams–Armondale telephone girl whose duties apparently went above and beyond the working of switchboard–as correspondent. 1919. Wilbert Garrison, 28, son of a wealthy publisher in New York, drove across country with a buddy and they holed up in the Armondale. A week later Wilbert left in his room his money, valuables, and a note indicating that he did not want to be a burden on others, and as such was ending his life. Despite the best efforts of the Nick Harris detective agency (who calls the cops in 1919), Wilbert is never found. 1930. Mrs. Louis Valenzuella, 40, ex-wife of Deputy Sheriff Valenzuella, is found dead in the Armondale of a suspected drug overdose. 1939. Washed-up boxer Louis Menney, 22, Armondale resident, is tackled by a priest after he sexually assaulted a 62 year-old woman in a church at 9th (now James M. Woods) and Green. Turns out he’d–moletsed? raped?–the papers will only mention “morals offenses”–a nine year-old in the church as well. Moreover, he’d done his business with a six year-old girl on the corner of 11th (now Chick Hearn) and Georgia, and also kidnapped and robbed an Agnes M—– and sexually assaulted a Margaret L—– in a church on West Adams; since the kidnapping charge is death penalty territory, we can only hope the Armondale’s most famous resident ended up in the proper hands.  1948. Francis Sylvester, of the Armondale, works across the street at the Western Union at 741 South Flower. Sylvester wires untold sums in care of himself to small outlying towns, where there are no Western Union offices, and destroys the records of the transactions. And 1965. Percy Hatch, 65, who had been in the hotel since 1957, started talking crazy-talk. As in, a loggorhea of obscenities for two straight weeks. Behind the Armondale registration desk was manager Nancy Furlow, 62, who, finally fed up with her repeated warnings, reached for the phone, and was shot dead by Hatch with one bullet. Hatch therewith turned the gun on himself. Shortly thereafter the Armondale was felled and a rather ill-advised Broadway was built on the site. Now a Macy’s, it resembles a Dawn mall on a slow day. For more on this exercise in brown, please go

1948. Francis Sylvester, of the Armondale, works across the street at the Western Union at 741 South Flower. Sylvester wires untold sums in care of himself to small outlying towns, where there are no Western Union offices, and destroys the records of the transactions. And 1965. Percy Hatch, 65, who had been in the hotel since 1957, started talking crazy-talk. As in, a loggorhea of obscenities for two straight weeks. Behind the Armondale registration desk was manager Nancy Furlow, 62, who, finally fed up with her repeated warnings, reached for the phone, and was shot dead by Hatch with one bullet. Hatch therewith turned the gun on himself. Shortly thereafter the Armondale was felled and a rather ill-advised Broadway was built on the site. Now a Macy’s, it resembles a Dawn mall on a slow day. For more on this exercise in brown, please go